What Would Tolstoy Say About AI Art?

Written by Vanessa Corrigall, Chat GPT 5.2 + Perplexity AI

A Conversation, a Process, and Why I’m Sharing How This Was Written

Lately, as I’ve been listening to What Is Art? by Leo Tolstoy, I’ve noticed something I can’t quite turn off. I’m not just following his arguments about art, emotion, and authenticity — I’m constantly testing them against the present moment. Against artificial intelligence. Against image generators. Against the kinds of tools artists are now expected to explain, justify, or defend.

This blog didn’t begin as a polished idea.

It began as a conversation with listening to an audiobook and talking with Chat GPT…as I walked my dog.

I want to be open about that — not because “transparency” is trendy, but because how ideas form feels inseparable from what we end up saying about art, tools, and authorship.

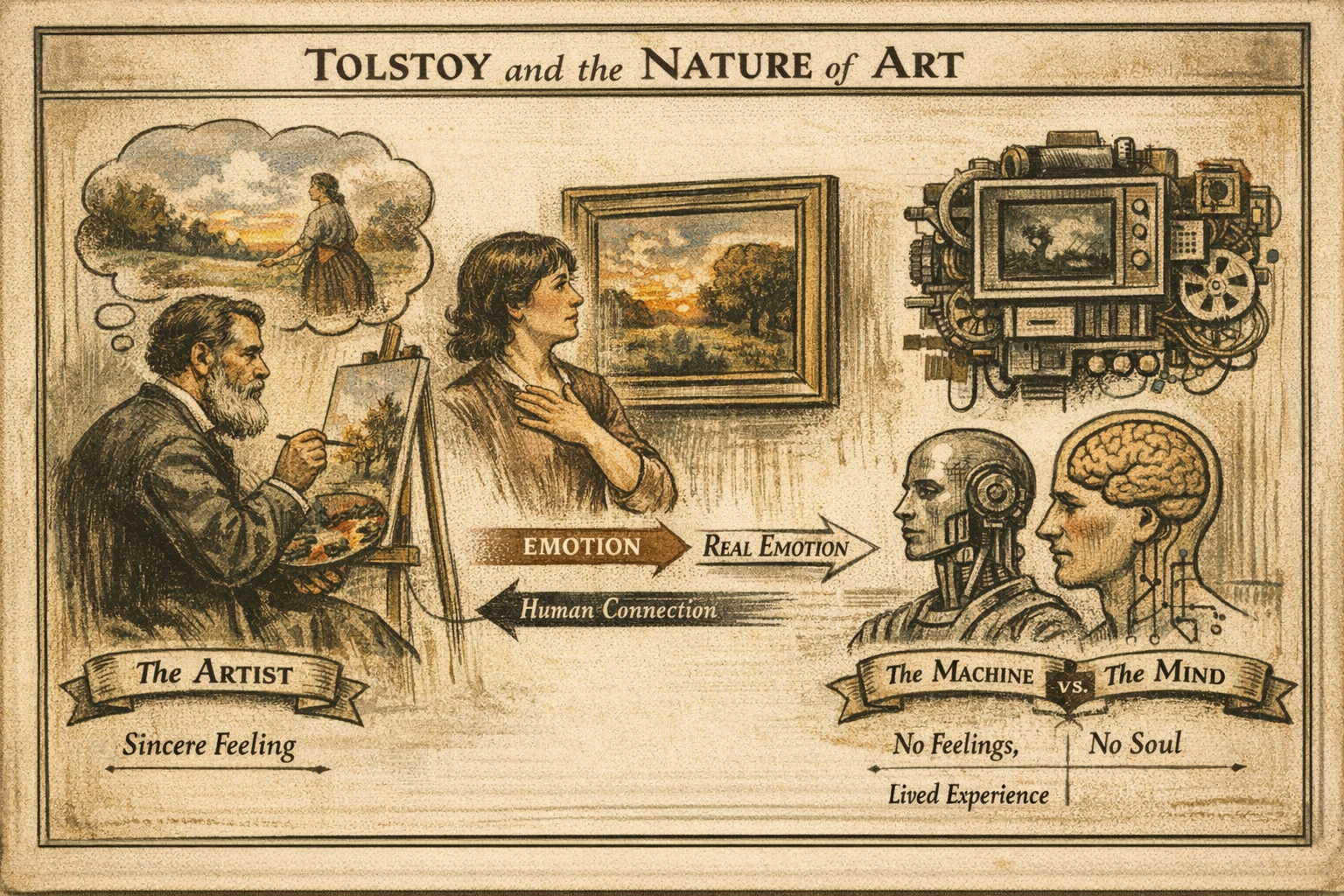

Tolstoy, Emotion, and “Real” Feeling

In What Is Art?, Tolstoy makes a demanding claim: art is art when it transmits a genuine feeling from one person to another. The source of that feeling can be imagined or remembered, vague or specific, but it must be sincerely felt by the person making the work. If the viewer “catches” that feeling, art has happened.

Listening to this, a question kept pressing in:

If the emotion is real for the viewer, does it matter how the image was made?

Tolstoy would almost certainly say yes. For him, the sincerity of the work comes from the artist’s inner life — from an actual human consciousness that suffers, hopes, remembers, believes. Tools don’t feel. Machines don’t have experiences they can willingly share. Under his framework, AI art doesn’t falter because it might be shallow or pretty; it falters because it has no lived, felt origin.

That’s a sharp, unsettling lens.

But it isn’t the only one.

When Form Matters More Than Feeling

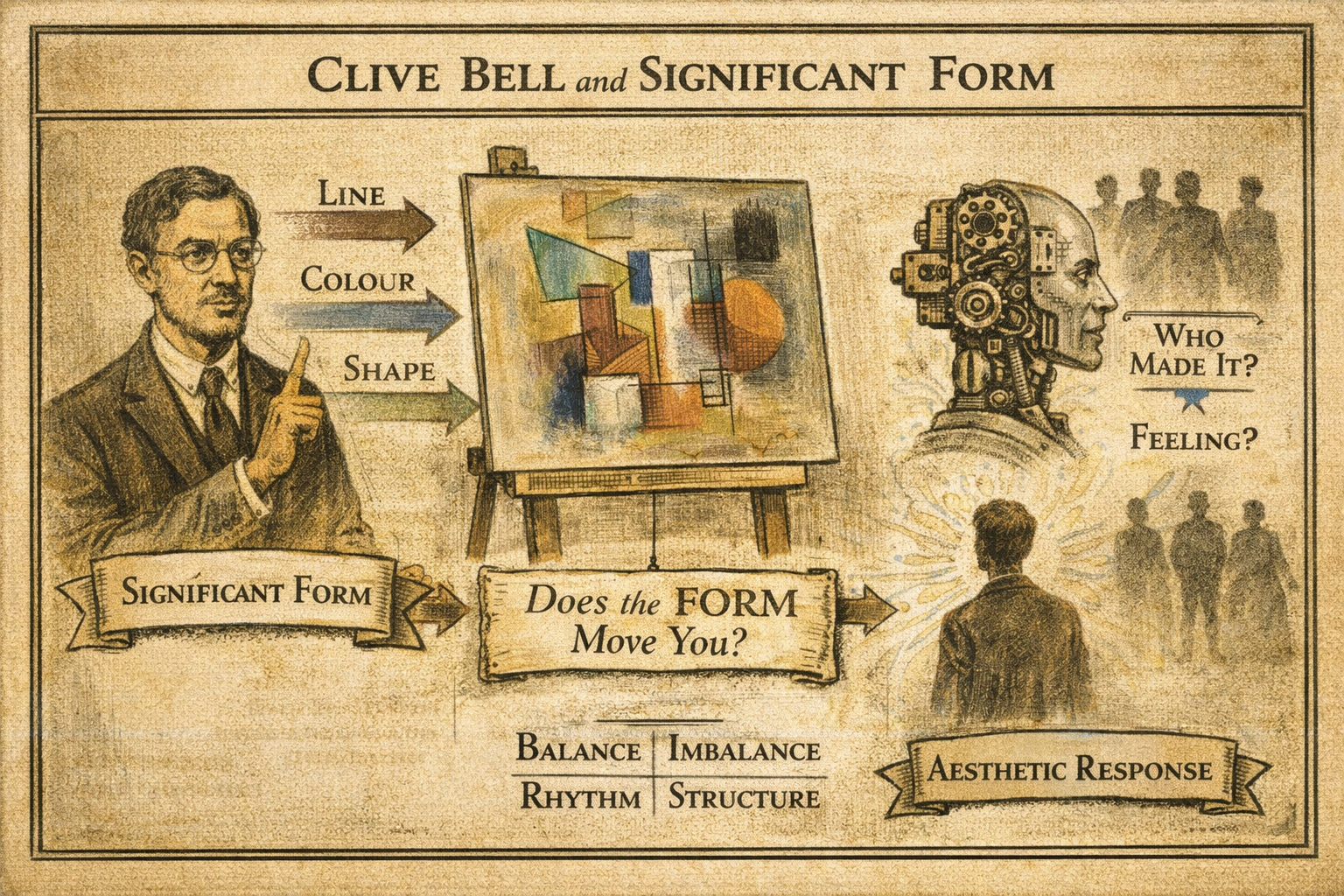

In the conversation that eventually became this post, another voice came in: Clive Bell.

Bell shifts the focus away from biography and sincerity. What matters for him is not the artist’s personal emotion, or their moral purpose, or even their story, but what he calls significant form: the arrangement of line, colour, shape, and structure that produces a distinct aesthetic response.

From Bell’s angle, the central question is not “Who made this?” or “What were they feeling?”

It’s much simpler, and much colder:

Does the form move you?

Seen this way, AI art doesn’t need a pre-emptive defence or a pre-emptive dismissal. It stands or falls on the strength of its composition, its rhythms of light and shadow, its balance and imbalance, its internal tensions and resolutions. If the visual orchestration works — if it generates that particular aesthetic charge — then, in Bell’s terms, the work works.

Put next to Tolstoy, the ground starts to shift.

Not because one of them is obviously wrong, but because art has never been governed by a single, stable rule.

Tolstoy vs. Bell: Two Ways of Understanding Art (and AI)

| Question | Leo Tolstoy | Clive Bell |

|---|---|---|

| What is art, at its core? | The transmission of a genuine human emotion from artist to viewer | The experience of significant form that provokes an aesthetic response |

| What matters most? | Sincerity of feeling and emotional authenticity | Formal arrangement: line, colour, shape, composition |

| Does the artist’s inner life matter? | Yes — art must originate in lived, felt human experience | No — biography, intention, and emotion are irrelevant |

| Is imagination allowed? | Yes, if the emotion behind it was genuinely felt | Irrelevant — imagination only matters if it produces strong form |

| Can art exist without emotion? | No — without emotional transmission, art fails | Yes — emotion may arise in the viewer, but isn’t required at the source |

| How is art judged? | By whether the viewer “catches” the artist’s sincere feeling | By whether the form generates aesthetic intensity |

| View of tools and technique | Secondary — tools serve expression but don’t define art | Central — technique and structure are core to artistic success |

| Likely view of AI art | Deeply skeptical: AI lacks lived emotion and human consciousness | Neutral to open: if the form works, the work works |

| Key weakness (by modern standards) | Risks excluding powerful experiences not tied to a single author | Risks ignoring ethics, authorship, and cultural context |

| Key strength today | Defends meaning, care, and human presence in art | Defends perception, visual power, and viewer experience |

Why I’m Telling You How This Was Written

All of this has left me thinking about process, not just product.

Recently, I attended professional development sessions for teachers encouraging artists and educators to disclose more about how their work is made: which tools they use, how ideas are generated, what collaborations or technologies are involved. The goal was to normalize process transparency — to make it part of how we talk about creative practice.

I’m torn about this.

On one hand, sharing process can build trust. It can demystify creative work and make it feel more accessible. On the other hand, it can easily turn into performance: every sketch, draft, or tool choice displayed like a provenance label, as if the behind-the-scenes itself is the work.

So I found myself asking a question:

Does disclosing the process actually help the reader think more clearly — or does it just give them one more story to manage?

For this post, I decided it does help, because the topic is already about authorship, origin, and legitimacy. This piece did not arrive fully formed. It emerged through dialogue, false starts, interruptions, revisions, and doubt. That feels relevant when we’re talking about what counts as “real” art, and who — or what — we think is allowed to make it.

Naming that process is part of the argument.

Old Aesthetic Debates, New Technological Questions

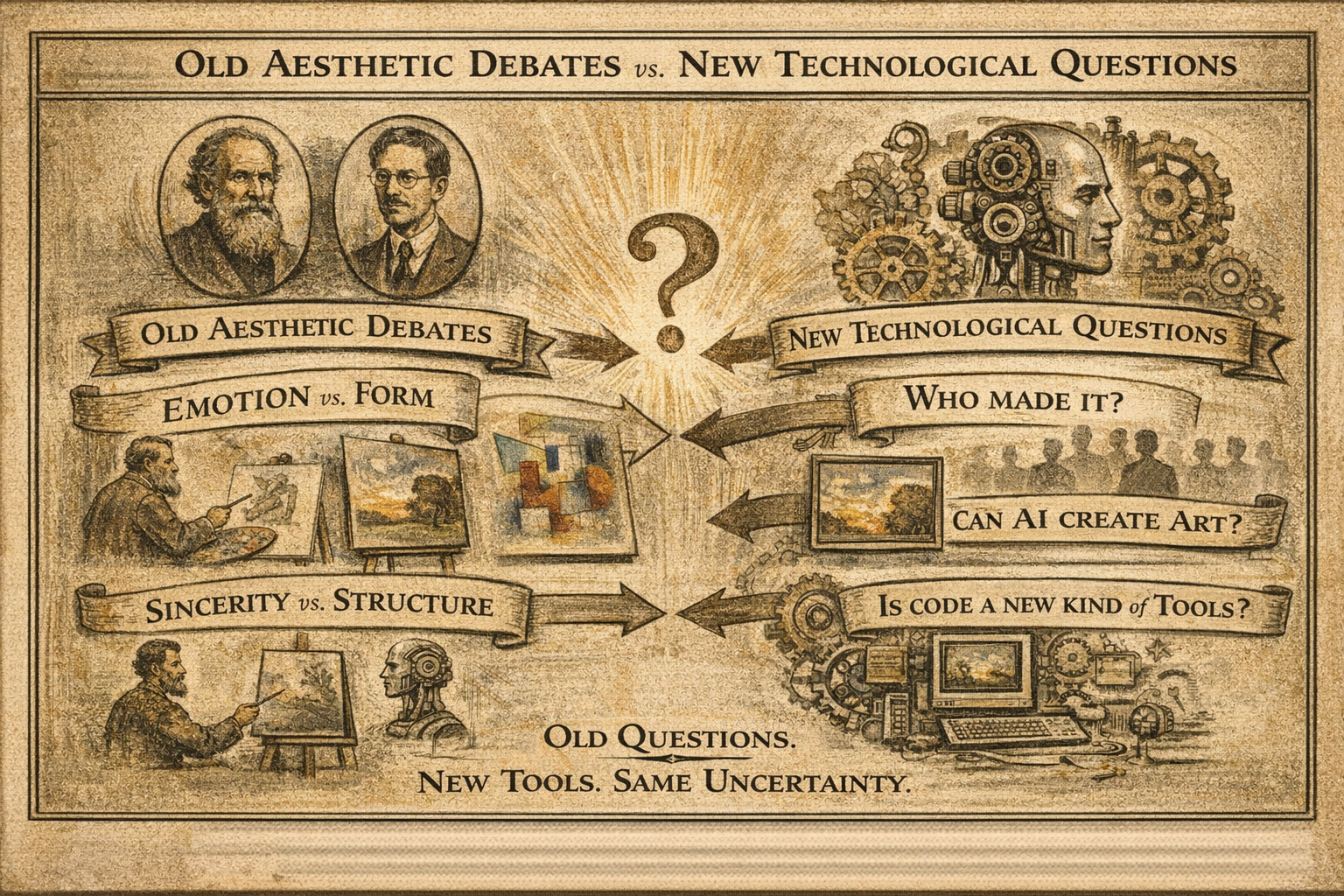

What keeps striking me is how old these “new” debates feel.

Long before AI, philosophers argued over fault lines like:

emotion vs. form

sincerity vs. structure

maker vs. experience

Artificial intelligence hasn’t invented a fresh crisis so much as it has reopened long-standing disagreements. Tolstoy offers one compass: art as sincere human feeling transmitted from one person to another. Bell offers another: art as significant form that provokes an aesthetic response, regardless of who made it.

Neither compass settles the question of AI art.

Neither was designed to.

But together, they reveal something important: our arguments about AI are also arguments about what we have always wanted art to do — comfort, disturb, connect, elevate, clarify, decorate, transform. The friction we feel now is simply that older definitions and values are colliding with new kinds of tools.

Sometimes the most honest stance isn’t a clean conclusion, but a tension you’re willing to inhabit.

Where I’m Landing (For Now)

At this point, I know that AI art cannot be judged through a single philosophical lens.

If you care most about emotional origin — about whether a work is rooted in a living, feeling consciousness — Tolstoy still has force. If you care most about visual experience — about what happens in your perception when you stand in front of a work — Bell still has force. In practice, if you’re a collector, educator, artist, or simply someone scrolling past images, you’re probably navigating both at once, whether you realize it or not.

This post is less a verdict than an invitation:

to slow down when you encounter AI-generated images

to notice which framework you instinctively reach for

to ask whether that framework actually fits the question you’re asking

Are you asking what counts as art?

What should count as art?

Or what moves you here and now?

A Question to Leave You With

The next time you encounter AI-generated art, pay attention to what you respond to first:

the emotion you feel in your body

the form you see — the composition, the colours, the shapes

or the story you’ve been told about how it was made

Your answer says a great deal — not just about AI, but about how you understand art itself, and what you most want it to be.